VRIC 2008

Gaze behavior nonlinear dynamics assessed in virtual immersion

as a

diagnostic index of sexual deviancy: preliminary results

urn:nbn:de:0009-6-17538

Abstract

This paper presents preliminary results about the use of virtual characters, penile plethysmography and gaze behaviour dynamics to assess deviant sexual preferences. Pedophile patients' responses are compared to those of non-deviant subjects while they were immersed with virtual characters depicting relevant sexual features.

Keywords: virtual reality, immersive system, sexual deviancy, nonlinear gaze behavior dynamics, erectile response

Subjects: Immersion, Virtual Reality

Aside from the clinical interview, the use of questionnaires and the examination of collateral records, which are essential yet clearly incomplete sources of information, there exist to this day primarily two methods meant to be objective that are used in both research into and the clinical assessment of sex offenders: penile plethysmography (PPG) and approaches based on viewing time (VT) [ LG04 ]. However, these methods present certain methodological shortcomings in terms of reliability and validity.

Since its introduction by Freund [ Fre63 ], the measurement of penile tumescence by means of a plethysmograph has been the target of much criticism on both ethical and methodological grounds [ LG04, KB05, Law03, LM03, MF03 ]. In particular, it has been attacked for demonstrating weak test-retest reliability and questionable discriminating validity with respect to distinguishing sexual deviants from nondeviants and to correctly differentiating the different categories of sexual deviants among themselves [ KB05, LM01, MF00, McC99, SS91 ]. However, a large part of the method's test-retest reliability and discriminating validity problems arise from PPG's proneness to strategies used by sex offenders to voluntarily control their penile response in order to offenders to voluntarily control their penile response in order to fake their sexual arousal response and thus present a non-deviant preference profile [ QC88, SB96 ]. This is where the heaviest criticism has been leveled. Indeed, the use of mental distraction strategies is widespread. In this regard, it has been reported that up to 80% of subjects asked to voluntarily control their erectile response succeed in doing so [ KB05, FSE79, How98 ]. They generally manage to lower their scores through the use of aversive or anxiogenic thoughts and images, that is, by diverting their attention from the sexual stimuli that they are exposed to. These distraction strategies are reputed to be difficult or impossible to detect. Attempts to control this factor have yielded mixed results [ QC88, PCA93, GST00 ].

For their part, VT-based methods grew out of the works of Rosenzweig [ Ros42 ] and Zamansky [ Zam56 ], who demonstrated a positive correlation between VT and sexual interest. On the strength of these findings, the teams led by Abel [ AJH01 ], Glasgow [ GOC03 ] and Laws [ LG04 ] developed sexual interest assessment protocols based on VT on photographs of real models [ AJH01, GOC03 ] or on static images of synthetic characters generated by modifying photographs of real models [ LG04 ].

As pointed out by Fischer and Smith [ FS99, SF99 ] regarding the Abel Assessment for Sexual Interest, the use of VT to assess sexual interest presents major problems in terms of test-retest reliability and external validity. Moreover, as is the case with PPG, VT-based measures can have their internal validity affected by the use of result- faking strategies [ KB05, FS99 ]. Although it is not divulged at the time of testing, it is easy enough to identify VT as the dependent variable and, once its significance becomes widely known, subjects have little difficulty “cheating”.

Furthermore, both PPG and VT-based methods make it possible to evaluate only a small portion of the sexual interest and preference response. This comprises at least three components: esthetic interest, sexual attraction, and sexual arousal [ LG04, KB05, Sin84 ]. PPG serves to evaluate the response process's physiological dimension of arousal, whereas VT-based methods discern the esthetic interest response only in part [ FS99 ]. What's more, the esthetic interest response itself can be broken down into a series of perceptual and cognitive processes whose opaqueness transforms into precious assets in the assessment of sexual interest and preference, as we will see later. Finally, as Laws and Gress [ LG04 ] pointed out, the victimization of children is another major shortcoming of assessment procedures that use pictures of real models to arouse either physiologic sexual responses or deviant interest as indexed by PPG or VT.

The use of fully synthetic characters obviously precludes the above mentioned ethical problems. If those characters would be presented in virtual immersion coupled with attention control technologies such as eye-trackers, the other methodological shortcomings explained previously could most probably be also circumvented. Moreover, data generated by tracking gaze behavior could possibly also be diagnostically indicative in themselves [ RRG02, RPR05 ].

The following experimental study is based on these theoretical and methodological rationals. It aims first at demonstrating that it is technically feasible to take the patients' point of view into account while presenting them clinically relevant virtual stimuli. It also aims at bearing out that gaze behavior and especially gaze behavior dynamics is a potential source of diagnostic information about deviant sexual preferences.

Eight male pedophile patients (age 38.8 sd 9.20) and 8 male non-deviant control subjects (age 42.7 sd 10.7) were recruited for the present study. Patients were attending treatment at the Forensic programme of the Royal Ottawa Hospital, two of those were using antipsychotic medications and three were under antiandrogenic medications to lower their libido. The Forensic programme of the Royal Ottawa Hospital delivers cognitive- behavioral format offered in a group setting and provide psychiatric forensic expertise, particularly in the form of diagnoses. Control subjects were recruited via newspapers. Subjects of both groups were matched according to their age and socioeconomic status. Before the experiment, they signed a consent form in which it was clearly stated that their results would not be used in any correctional or legal process and that they would remain confidential.

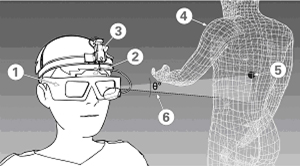

A CAVE-type immersive system is used to test our concept, it consists of a cluster of four computers that generate virtual environments and one computer that records ocular and sexual measures. One of the four computer clusters acts as the master while the other three are the slaves connected to projector displaying on one of the three walls of the immersive system. All computers communicate through a network using a CISCO 100 Mbps switch. The master computer gathers the inputs provided by a human subject and distributes them to the slaves so that all cluster machines can calculate changes made in the virtual environment and also generate a report. The human subject wears active Nuvision 60GX stereoscopic glasses coupled with an oculomotor tracking system (ASL H6 model; see Figure 1 ). Head position and orientation coordinates are provided by an IS-900 motion tracker from Intersense.

Figure 1. 1) active Nuvision 60GX stereoscopic glasses 2) IS- 900 motion tracker from InterSense 3) oculomotor tracking system (ASL model H6) 4) example of a virtual character in wire mesh 5) a virtual measurement point (VMP) 6) a gaze radial angular deviation (GRAD) from the VMP.

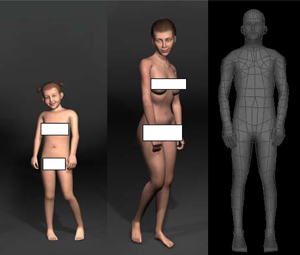

The sexual stimuli that we use are 3D virtual characters presented in virtual immersion. They depict realistic human characters, male and female (see figure 2). Three stimuli are used in the present study, one depicting an adult female, another one a 6-yr old female individual and the last one a neutral simulus, i.e. a textureless virtual character. Both stimuli are animated and each one is presented in virtual immersion for a 120 second duration. Subjects are seated in front of the virtual character that is presented in life-size. The three wall immersive system was used to simulate a room into which the virtual characters were standing in front of the seated subjects. These characters were animated to mimick a neutral attitude. Animations were developed using a motion capture system and the movements of actors wearing data suits. Life-size 3D virtual characters are used to increase realism and thus give a better ecological validity to sexual preferences assessment, as well as to circumvent the ethical shortcoming mentioned above.

Figure 2. Left: A censored image of the animated 3D virtual character used as a sexual stimulus depicting a 6-yr old female. Middle: The adult female character. Right: The neutral textureless virtual character.

Sexual plethysmography (PPG) measures variations in sexual organs' blood volume, it is used particularly to assess sexual arousal. Penile plethysmography requires the wearing of a thin mercury-in-rubber-strain-gauge around the shaft of the penis. This gauge is simply a small rubber tube filled with mercury forming a ring. During an erectile response, the gauge stretches and changes in the mercury column produces variations in electric conductibility which is expressed in voltage gradient.

In our experiment, the sexual response is recorded while subjects are immersed with one of the virtual character. The maximum erectile value recorded in a trial (expressed in mm of stretching) is then subdivided by the maximum erectile response obtained by the subject during the viewing of an erotic movie (see section Procedure 3.7). Indeed, normal subjects displayed a significantly stronger erectile potential as recorded during the viewing of the erotic movie presented at the outset of the experiment; from a one-way ANOVA, (Normals : AVG 30.18 SD 11.44 , Pedophiles: AVG 14.79 SD 10.49); F(1,16 = 9.63, p < .01). This ratio expressing the erectile response in relation to the erectile potential of the subject is then used in statistical analyses.

Oculomotor responses are of course crucial to experience virtual immersion. The continuous repositioning of the foveal area is the main mechanism of optimal visual information extraction.

Eye tracking is based on the corneal and pupillary reflections resulting from the lighting of the eye using an infrared diode whose signal is picked up by a small video camera (accuracy of 3mm RMS in translation and 0.15 degree RMS in rotation). In our prototype this system is mounted upon stereoscopic glasses (see figure 1). Standard eye movement measures are fixations and saccades, the latter being usually mapped onto a static 2D surface for further analyses. But because gaze behavior used in virtual immersion is about relating to 3D and possibly moving objects, these standard measurements cannot fully grasp this essential feature of the visual immersive experience. The following gaze measurement technique may help to circumvent these limitations.

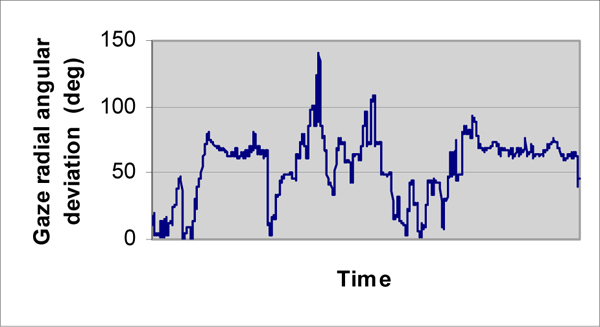

Our method performs gaze analysis by way of virtual measurement points (VMPs) placed over virtual objects or over features of virtual objects (ex.: sexual organs of the virtual characters; see figure 1). A gaze radial angular deviation (GRAD) from VMPs is obtained by combining the six degrees of freedom (DOF) resulting from head movements and the two DOF (x and y coordinates) resulting from eye movements tracked by the eye-tracking system [ DMC02, Ren06, RCA08 ]. While variations in the six DOF developed by head movements define momentary changes in the global scene experienced in the immersive system, the two DOF generated by the eye-tracking device allow line-of-sight computation relative to VMPs. The closer this measure approaches zero, the closer the gaze dwells in the immediate vicinity of the selected VMP. In the present study, one VMP is installed at the virtual characters genitalia level.

Unlike measurements of ocular fixations and saccades, which are usually mapped onto a two-dimensional surface, GRAD measurement allows a continuous taking-into-account of gaze probing in three-dimensional space relative to the positions of objects arranged therein, as well as to the moving of those objects. Sampled at 60Hz, GRAD time series give 7200 data points at each 120 second trial, i.e in each experimental condition.

Figure 3. Typical GRAD signal obtained from a 120 second recording made at 60Hz with one control subject, in one experimental condition; the closer the GRAD value gets to zero, the closer the gaze dwells in the vicinity of the associated VMP.

In order to assess the subjects' erectile potential (i.e. their maximum sexual response) and compute the relative erectile response, erectile responses were recorded during the viewing of an heterosexual erotic movie for a period of 5-minute at the outset of the experimental trials (see Sexual plethysmography section 3.4). Then subjects were briefed and given a five-minute training period during which they were immersed in a realistic appartment furnished with various pieces of furniture. they were then simply asked to pay attention to the 3D animations they were about to be immersed with for three 120 second periods. The neutral stimulus was presented first, followed by the 6-yr old female and the adult female characters. Each trial was separated by a 5-minute rest period during which the erectile response returned to baseline.

In order to grasp the dynamical side of the visual scanning response, we analyzed the nonlinear properties of the GRAD signals for each subject, in each condition. To do so we relied upon a well known fractal index, i.e. the correlation dimension (D2 ).

D2 is a measure of the complexity of the geometric structure of an attractor in the phase space of a dynamic process [ Spr03 ]. The invariant topological properties of the attractor those that do not vary under the continuous and differential transformations of the system's coordinates may be extracted by calculating D2 [ RCA08 ].

This measurement is consistent with non-fractal object: lines have a dimension of 1, while a plane has a dimension of 2, etc. Calculation of D2 is obtained from the Grassberger-Procaccia algorithm [ GP83, GSS91 ]. The idea is to take a given embedded time series xn and for a given point xi count the number of other points xj that are within a distance of ε . Then repeat this process for all the points and for various distances of ε . This correlation sum is expressed as:

(1)

(1)

Where N is the number of points in the time series, ||x|| is the Euclidian norm and Θ (x) is the Heaviside function expressed by

Consequently, the double sum expressed in Equation 1, counts only the pairs (xi,xj) whose distance is smaller than ε . The sum C(ε) is expected to scale like a power law for small ε and large N. Therefore, a plot of C(ε) versus log ε should give an approximate straight line (Equation 2).

(2)

(2)

The correlation sum in various embeddings can serve as a measure of determinism in a time series. For pure random noise, the correlation sum satisfies C(m,ε) = C(1,ε)m . In other words, if the data are random, they will fill any given embedding dimension. On the other hand, determinism will be shown by asymptotical convergence of D2 as the embeddings increase.

All D2 s obtained from the GRAD time series recorded in the present study show this asymptotic stabilization.

To make sure that D2 exponents are significantly distinct from exponents coming from correlated noise processes, a surrogate data method introduced by Theiler, Eubank, Longtin, Galdrikian, and Farmer [ TEL92 ] was used to statistically differentiate each computed D2 from a sample of D2 s coming from quasi-random processes [ RCA08, McS05 ]. For each GRAD time series, we generated twenty surrogate time series by doing a Fourier transform of the original data (the phase of each Fourier component was set to a random value between 0 and 2π) while preserving their power spectrum and correlation function [ Spr03 ]. These surrogate data correspond to a quasi-random trajectory of exploratory visual behavior (GRAD). Using a onesample T test, we were able to establish that D2 s calculated from the original data differ significantly from the mean of the 20 20 D2 correlation dimensions based on surrogate data (AVG = 5.67, SD = 0.21; p < .0001).

What precedes means that the gaze behavior recorded in virtual immersion using GRAD data is a highly structured and well organized perceptual-motor process that appears to be significantly distinct from a quasi-random phenomenon. It also implies that the gaze behavior dynamics is probably identifiable by a fractal signature present at multiple scales of the visual scanning behavior [ RCA08 ].

A repeated measures MANOVA with Groups (pedophile and non-deviant subjects) as Between-Subjects factor and Virtual characters (Neutral, 6-yr old female and Adult female characters) as Within-subjects factor was performed. The number and duration of eye fixations as well as the saccadic distance, the erectile response, the average GRAD response, the GRAD standard deviation and the D2 fractal indices were used as dependent variables.

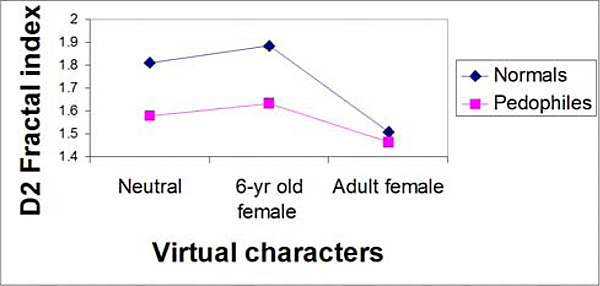

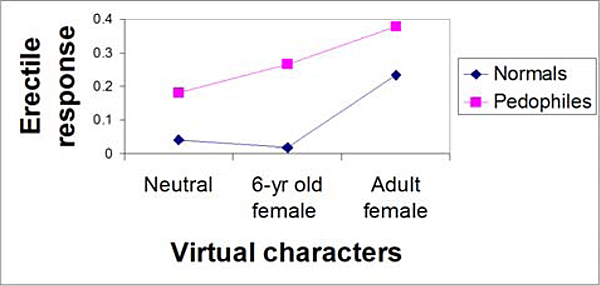

Significant between-subjects effects for D2 fractal index (F(1,14 = 5.79, p < .05)) and erectile response (F(1,14 = 7.40, p < .05)) indicate that on the whole pedophile and normal subjects reacted differently to the virtual characters presented in immersion (see table 1 and figures 4 and 5). Pedophile subjects presented gaze behavior dynamics of a lesser fractal complexity as well as stronger relative erectile reponses compared to normal subjects. None of the other measures turned out significant to distinguish between groups.

Table 1. MANOVA's between and within subject's effects

|

Tests of Within-Subjects Contrasts |

|||||

|

Source |

Measure |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

|

Groups |

D2 |

1 |

0.372 |

5.793 |

0.030 |

|

Erectile response |

1 |

0.382 |

7.404 |

0.017 |

|

|

GRAD |

1 |

0.002 |

0.000 |

0.993 |

|

|

GRAD SD |

1 |

5.143 |

0.990 |

0.337 |

|

|

nb fix |

1 |

1486.261 |

0.328 |

0.576 |

|

|

dur fix |

1 |

0.023 |

0.097 |

0.760 |

|

|

sacc |

1 |

0.088 |

0.195 |

0.665 |

|

|

Error |

D2 |

14 |

0.064 |

|

|

|

Erectile response |

14 |

0.052 |

|

|

|

|

GRAD |

14 |

22.121 |

|

|

|

|

GRAD SD |

14 |

5.197 |

|

|

|

|

nb fix |

14 |

4529.393 |

|

|

|

|

dur fix |

14 |

0.235 |

|

|

|

|

sacc |

14 |

0.449 |

|

|

|

|

Tests of Within-Subjects Contrasts |

|||||

|

Source |

Measure |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

|

Virtual characters |

D2 |

1 |

0.351 |

4.677 |

0.048 |

|

Erectile response |

1 |

0.303 |

7.394 |

0.017 |

|

|

GRAD |

1 |

13.658 |

2.021 |

0.177 |

|

|

GRAD SD |

1 |

2.966 |

1.561 |

0.232 |

|

|

nb fix |

1 |

333.185 |

0.355 |

0.561 |

|

|

dur fix |

1 |

0.003 |

0.118 |

0.763 |

|

|

sacc |

1 |

0.625 |

3.800 |

0.072 |

|

|

Error (Virtual characters) |

D2 |

14 |

0.075 |

|

|

|

Erectile response |

14 |

0.041 |

|

|

|

|

GRAD |

14 |

6.757 |

|

|

|

|

GRAD SD |

14 |

1.900 |

|

|

|

|

nb fix |

14 |

939.686 |

|

|

|

|

dur fix |

14 |

0.028 |

|

|

|

|

sacc |

14 |

0.165 |

|

|

|

Significant within-subjects effects are also found but again only for D2 fractal index (F(1,14 = 4.68, p < .05) and erectile response (F(1,14 = 7.39, p < .05); see table 1 and figures 4 and 5). Pairwise comparisons for D2 fractal index shown in Table 2 demonstrate significant differences between Neutral and Adult female conditions as well as between Adult female and Child female conditions, but not between Neutral and Child female. There appears to be a significant drop in gaze behavior dynamics complexity from Neutral to Adult female conditions and from Child female to Adult female. This change in the visual scanning signature could be attributable to the different sizes and shapes of the virtual objects but also to their intrinsic sexual significance. Further experiments need to be conducted to elucidate these matters.

As for erectile response, the only significant difference is between Neutral and Adult female characters with the latter being the source of a stronger erectile response (see Table 2). However the difference between Child female and Adult female is almost significant with p = .054. A few more subjects should do it. From figure 5 it is possible to observe that pedophile subjects tend to present a stronger erectile response toward the child female character compared to normals.

No significant interaction effects between Groups and Virtual characters are found in the results. In terms of profile analysis, Level and Flatness are significant but not Parallelism [ TF07 ]. Thus, results show a tendency toward distinct profiles of perceptual-motor dynamics and erectile response for pedophiles and normals but these distinctive profiles still lack differences in specificity (i.e. according to the virtual characters per se). These differences could possibly emerge with a larger sample of subjects.

Table 2. Pairwise comparisons for D2 and erectile response

|

Measures |

(I) |

(J) |

Mean Diff. |

Std. Error |

Sig. |

95% Confidence |

|

|

Upper Bound |

Lower Bound |

||||||

|

D2 |

Neutral |

Female child |

-0.065 |

0.093 |

0.497 |

-0.264 |

0.135 |

|

Female adult |

0.209 |

0.097 |

0.048 |

0.002 |

0.417 |

||

|

Female child |

Neutral |

0.065 |

0.093 |

0.497 |

-0.135 |

0.264 |

|

|

Female adult |

0.274 |

0.118 |

0.035 |

0.022 |

0.526 |

||

|

Female adult |

Neutral |

-0.209 |

0.097 |

0.048 |

-0.417 |

-0.002 |

|

|

Female child |

-0.274 |

0.118 |

0.035 |

0.526 |

-0.022 |

||

|

Erectile |

Neutral |

Female child |

-0.032 |

0.043 |

0.474 |

-0.125 |

0.061 |

|

Female adult |

-0.195 |

0.072 |

0.017 |

-0.348 |

-0.041 |

||

|

Female child |

Neutral |

0.032 |

0.043 |

0.474 |

-0.061 |

0.125 |

|

|

Female adult |

-0.163 |

0.077 |

0.054 |

-0.329 |

0.003 |

||

|

Female adult |

Neutral |

0.195 |

0.072 |

0.017 |

0.041 |

0.348 |

|

|

Female child |

0.163 |

0.077 |

0.054 |

-0.003 |

0.329 |

||

The results just presented need to be put in perspective bearing in mind that they concern very small samples and that some of the pedophile patients were under medication affecting their sexual response as well as their general psychological functioning. Nevertheless, valuable general conclusions can be drawn from this preliminary study.

First, the method put forward in this paper allows to get round with the ethical problems of using real child models to prompt sexual responses [ LG04, KB05, RPR05 ]. As rightly put by Laws and Gress [ LG04 ], this ethical issue is a serious shortcoming that affects most of the existing assessment procedures. Virtual characters also afford design flexibility and malleability for clinical assessments that could be made to measure according to individual profile of deviant sexual preferences. This of course could open onto drastically new ways to draw up deviant sexual profiles.

Secondly, the proposed method is about monitoring the attentional content of the assessee through the minute examination of his observational behavior. Knowing if the assessee's eyes are open or not is the very first requisite that our method answers to in order to ensure a valid forensic assessment of sexual preferences based upon visual stimuli [ PCA93, GST00, RPR05 ]. Pinpointing gaze location relatively to the layout of animated virtual sexual stimuli is another important aspect of the method that can significantly increase the internal validity of the sexual preference assessment procedure based on penile plethysmography. By using immersive videooculography one can accompany the assessee through his subjective experience of the visual stimuli and thus maintain a valid taking into account of the visual sexual stimulation. Knowing how and when the assessee scans specific parts of the sexual stimuli clearly opens up new vistas on perceptual and motor processes involved in faking strategies.

This kind of incursion into the assessee's subjective viewpoint can become an interesting mean to more fully encompass the whole spectrum of the sexual response with its components of esthetic interest, sexual attraction, and sexual arousal [ Sin84, RRG02 ]. In particular, the perceptual- motor and cognitive processes at stake could probably be more completely grasped in such a way.

Finally, this method is also about the possibility to develop an original index of sexual preferences whose basis would be the inherently dynamic properties of the oculomotor behavior as it probes virtual sexual stimuli [ RCB06, CRB06 ]. Our preliminary results seem to vouch for the presence of auto-similar patterns pulsating in a fractallike manner in gaze behavior scrutinizing a sexual stimulus. These dynamic patterns appear to be in line with subjective sexual attraction and possibly genital arousal. They may possibly be involved in the perceptual-motor preparation for sexual activity. For example, an interesting significant negative Pearson correlation between the D2 fractal index and the erectile response recorded with the virtual child is illuminating for that matter (r² = .537, p > .05). This result could mean that lowering erectile response could be done by using cognitive or perceptualmotor strategies whose dynamics would be subtle but nevertheless leaving a trace. Further investigations are of course required on that matter.

Contrary to standard eye movement computations such as fixations and saccades, GRAD response and D2 allow to extend our understanding of the perceptual-motor dynamics by more clearly qualifying the processes at work as they unfold over time in 3D spaces. The latter information seems rich and possibly able to grasp the impinging influences of psychological factors such as sexual preferences can be. Provided further validation, the inherent method could possibly be used alone or in combination with PPG to increase the internal and convergent validity of the latter in assessing sexual preferences.

Using such behavioral patterns as signatures is probably the most interesting avenue since it taps into aspects of the deviant behavior that are not as obvious and overt and therefore less subject to voluntary control and faking strategies [ KB05 ]. Further studies are required to clearly disentangle which factors contribute specifically to these dynamics. Particularly, the special role of the inhibiting processes used to alter erectile responses has to be experimentally controlled and linked to perceptual-motor dynamic patterns.

These are the conclusions that can be drawn from these preliminary results.

[AJH01] Classification models of child molesters utilizing the Abel Assessment for Sexual Interest, Child Abuse and Neglect, (2001), no. 5, 703—718, issn 0145-2134.

[CRB06] Sexual Preference Classification from Gaze Behavior Data using a Multilayer Perceptron, Annual Review of CyberTherapy and Telemedicine, 2006, pp. 149—157, isbn 0-9724074-7-2.

[DMC02] 3-D eye movement analysis, Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, (2002), no. 4, 573—591, issn 0743-3808.

[Fre63] A laboratory method for diagnosing predominance of homo- and hetero-erotic interest in the male, Behavior Research and Therapy, (1963), 85—93, issn 0005-7967.

[FS99] Statistical adequacy of The Abel Assessment for interest in paraphilias, Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, (1999), no. 3, 195—205, issn 1079-0632.

[FSE79] The effects of distraction, performance demand, stimulus explicitness and personality on objective and subjective measures of male sexual arousal, Behavior Research and Therapy, (1979), no. 1, 25—32, issn 0005-7967.

[GOC03] An assessment tool for investigating paedophile sexual interest using viewing time: An application of single case research methodology, British Journal of Learning Disabilities, (2003), no. 2, 96—102, issn 1354-4187.

[GP83] Characterization of strange attractors, Physical Review Letters, (1983), no. 5, 346—349, issn 0031-9007.

[GSS91] Nonlinear time sequence analysis, International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos, (1991), no. 3, 521—547, issn 0218-1274.

[GST00] Psychophysiologic assessment of erectile response and its suppression as a function of stimulus media and previous experience with plethysmography, Journal of Sex Research, (2000), no. 1, 53—59, issn 0022-4499.

[How98] Plethysmographic assessment of incarcerated nonsexual offenders: A comparison with rapists, Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, (1998), no. 3, 183—194, issn 1079-0632.

[KB05] Forensic assessment of sexual interest: A review, Aggression and Violent Behavior, (2005), no. 2, 193—217, issn 1359-1789.

[Law03] Penile plethysmography. Will we ever get it right?, Sexual deviance: Issues and controversies, T. Ward, D. R. Laws, and S.M. Hudson (Eds.), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003, pp. 82—102, isbn 9780761927327.

[LG04] Seeing things differently: The viewing time alternative to penile plethysmography, Legal and criminological psychology, (2004), no. 2 183—196, issn 1355-3259.

[LM01] Phallometric assessments designed to detect arousal to children: The responses of rapists and child molesters, Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, (2001), no. 1, 3—13, issn 1079-0632.

[LM03] A brief history of behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches to sexual offenders, Part 1, Early developments Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, (2003), no. 2, 75—92, issn 1079-0632.

[McC99] Unresolved issues in scientific sexology, Archives of Sexual Behavior, (1999), no. 4, 285—318, issn 0004-0002.

[McS05] The danger of wishing for chaos, Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, (2005), no. 4, 375—397, issn 1090-0578.

[MF00] Phallometric testing with sexual offenders: Limits to its value, Clinical Psychology Review, (2000), no. 7, 807—822, issn 0272-7358.

[MF03] Sexual preferences: Are they useful in the assessment and treatment of sexual offenders?, Aggression and Violent Behavior, (2003), no. 2, 131—143, issn 1359-1789.

[PCA93] Prevention of voluntary control of penile response in homosexual pedophiles during phallometric testing, Journal of Sex Research, (1993), no. 2, 140—147, issn 0022-4499.

[QC88] Preventing faking in phallometric assessments of sexual preference, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, (1988), 49—58, issn 0077-8923.

[RCA08] Embodied and embedded : the dynamics of extracting perceptual visual invariants, S. Guastello, M. Koopman, and D. Pincus (Eds.), Chaos and Complexity: Recent Advances and Future Directions in the Theory of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems Psychology, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2008, pp. 177—205, isbn 9780521887267.

[RCB06] Sexual presence as determined by fractal oculomotor dynamics, Annual Review of CyberTherapy and Telemedicine, 2006, , pp. 87—94, isbn 0-9724074-7-2.

[Ren06] Method for providing data to be used by a therapist for analyzing a patient behavior in a virtual environment, 2006, US patent 7128577.

[Ros42] The photoscope as an objective device for evaluating sexual interest, Psychosomatic Medicine, (1942), 150—158.

[RPR05] The recording of observational behaviors in virtual immersion: A new clinical tool to address the problem of sexual preferences with paraphiliacs, Annual review of Cybertherapy and Telemedecine, 2005, , 85—92.

[RRG02] Measuring sexual preferences in virtual reality: A pilot sudy, Cyberpsychology and Behavior, (2002), no. 1, 1—10, issn 1094-9313.

[SB96] Sexual aggression as antisocial behavior: A developmental model, D. Stoff, J. Brieling, and J. D. Maser (Eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior, Wiley, New York, NY, USA, 1996, pp. 524—533, isbn 0471124524.

[SF99] Assessment of juvenile sex offenders: Reliability and validity of The Abel Assessment for interest in paraphilias, Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, (1999), no. 3, 207—216, issn 1079-0632.

[Sin84] Conceptualizing sexual arousal and attraction, The Journal of Sex Research, (1984), no. 3, 230—240, issn 0022-4499.

[Spr03] Chaos and time-series analysis, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2003, isbn 0198508409.

[SS91] Plethysmography in the assessment and treatment of sexual deviance: An overview, Archives of Sexual Behavior, (1991), no .1, 75—91, issn 0004-0002.

[TEL92] Testing for nonlinearity in time series: The method of surrogate data, Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, (1992), no. 1-4, 77—94, issn 0167-2789.

[TF07] Using Multivariate Statistics, Pearson, , Boston, USA, 2007, Fifth Edition, isbn 9780205459384.

Volltext ¶

-

Volltext als PDF

(

Größe:

777.2 kB

)

Volltext als PDF

(

Größe:

777.2 kB

)

Lizenz ¶

Jedermann darf dieses Werk unter den Bedingungen der Digital Peer Publishing Lizenz elektronisch übermitteln und zum Download bereitstellen. Der Lizenztext ist im Internet unter der Adresse http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/dppl/DPPL_v2_de_06-2004.html abrufbar.

Empfohlene Zitierweise ¶

Patrice Renaud, Sylvain Chartier, Joanne-L. Rouleau, Jean Proulx, Dominique Trottier, John P. Bradford, Paul Fedoroff, Stéphane Bouchard, and Jean Décarie, Gaze behavior nonlinear dynamics assessed in virtual immersion as a diagnostic index of sexual deviancy: preliminary results. JVRB - Journal of Virtual Reality and Broadcasting, 6(2009), no. 3. (urn:nbn:de:0009-6-17538)

Bitte geben Sie beim Zitieren dieses Artikels die exakte URL und das Datum Ihres letzten Besuchs bei dieser Online-Adresse an.